Genetic researchers at the European Molecular Biology Lab (EMDL) have shown that mammalian life begins differently than originally suspected.

It was long hypothesized that during a mammal embryo's first cell division, one spindle is responsible for segregating the embryo's chromosomes into two cells. Researchers now show that there are actually two spindles (as shown below), one for each set of parental chromosomes, meaning that the genetic information from each parent is kept apart throughout the first division.

The publication Science published the results (which are likely to change biology textbooks) on 7/12/18. {Are there still textbooks?!}.

This dual spindle formation may explain the high error rate in the early developmental stages of mammals, spanning the first few cell divisions. "The aim of this project was to find out why so many mistakes happen in those first divisions," says Dr. Jan (a guy!) Ellenberg, the group leader at EMBL who led the project. "We already knew about dual spindle formation in simpler organisms like insects, but we never thought (why not?!) this would be the case in mammals like mice. This finding was a big surprise, showing that you should always be prepared for the unexpected."

Researchers have heretofore seen parental chromosomes occupying two half-moon-shaped parts in the nucleus of two-cell embryos, but it wasn't clear how this could be explained. "First, we were looking at the motion of parental chromosomes only, and we couldn't make sense of the cause of the separation," said Dr. Judith Reichmann. "Only when focusing on the microtubules -- the dynamic structures that spindles are made of -- could we see the dual spindles for the first time. This allowed us to provide an explanation for this 20-year-old mystery."

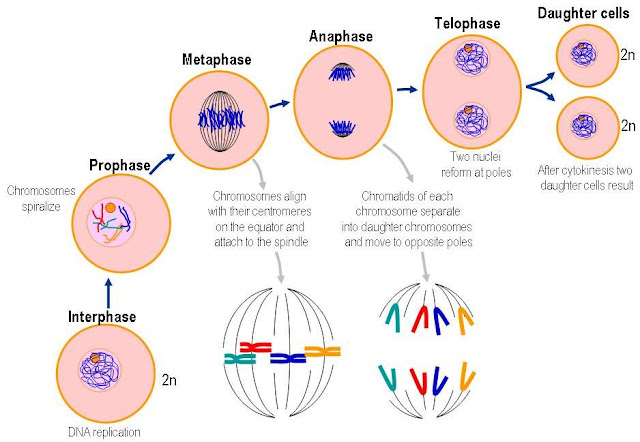

Mitosis is the process of cell division, when one cell splits into two daughter cells. It occurs throughout the lifespan of multi-cellular organisms but is particularly important when the organism grows and develops. The key step of mitosis is to pass an identical copy of the genome to the next cell generation. For this to happen, DNA is duplicated and organised into dense thread-like structures known as chromosomes. The chromosomes are then attached to long protein fibres -- organised into a spindle -- which pulls the chromosomes apart and triggers the formation of two new cells. {The following diagram is one which will likely be updated in future embryology textbooks.}

The spindle is made of thin, tube-like protein assemblies known as microtubules. During mitosis of animal cells, groups of such tubes grow dynamically and self-organize into a bi-polar spindle that surrounds the chromosomes. The microtubule fibres grow towards the chromosomes and connect with them, in preparation for chromosome separation to the daughter cells. Normally there is only one bi-polar spindle per cell, however, this research suggests that during the first cell division there are two: one each for the maternal and paternal chromosomes.

"The dual spindles provide a previously unknown mechanism -- and thus a possible explanation -- for the common mistakes we see in the first divisions of mammalian embryos," Dr. Ellenberg explains. Such mistakes can result in cells with multiple nuclei, terminating development. "Now, we have a new mechanism to go after and identify new molecular targets. It will be important to find out if it works the same in humans, because that could provide valuable information for research on how to improve human infertility treatment, for example."

In addition, the knowledge from this paper might impact legislation. In some countries, the law states that human life begins -- and is thus protected -- when the maternal and paternal nuclei fuse after fertilization. If it turns out that the dual spindle process works the same in humans, this definition is not fully accurate, as the union in one nucleus happens slightly later, after the first cell division.

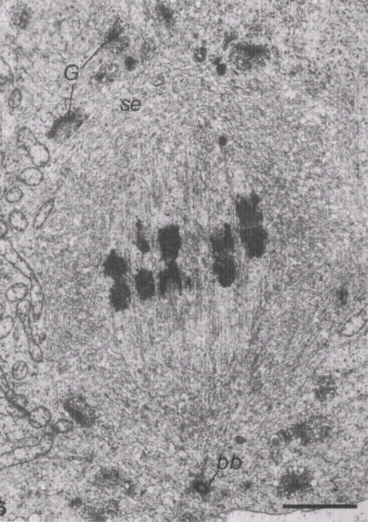

This discovery would have been impossible without the light-sheet microscopy technology (as seen above) developed at EMBL, which is now available through the spin-off company Luxendo. This allows for real-time and 3D imaging of the early stages of development, when embryos are very sensitive to light and would be damaged by conventional light microscopy methods. The high speed and spatial precision of light-sheet microscopy drastically reduce the amount of light that the embryo is exposed to, making a detailed analysis of these formerly hidden processes possible.

This is one spin we can stay with for awhile.

Steph

Earthquake experiment with brownies representing the stable craton of Canada and jello representing the tectonic plate boundary in Haiti.

The kids made "earthquake-proof" structures and observed the differences of the structures on "Canada" and "Haiti."

It was long hypothesized that during a mammal embryo's first cell division, one spindle is responsible for segregating the embryo's chromosomes into two cells. Researchers now show that there are actually two spindles (as shown below), one for each set of parental chromosomes, meaning that the genetic information from each parent is kept apart throughout the first division.

The publication Science published the results (which are likely to change biology textbooks) on 7/12/18. {Are there still textbooks?!}.

This dual spindle formation may explain the high error rate in the early developmental stages of mammals, spanning the first few cell divisions. "The aim of this project was to find out why so many mistakes happen in those first divisions," says Dr. Jan (a guy!) Ellenberg, the group leader at EMBL who led the project. "We already knew about dual spindle formation in simpler organisms like insects, but we never thought (why not?!) this would be the case in mammals like mice. This finding was a big surprise, showing that you should always be prepared for the unexpected."

Researchers have heretofore seen parental chromosomes occupying two half-moon-shaped parts in the nucleus of two-cell embryos, but it wasn't clear how this could be explained. "First, we were looking at the motion of parental chromosomes only, and we couldn't make sense of the cause of the separation," said Dr. Judith Reichmann. "Only when focusing on the microtubules -- the dynamic structures that spindles are made of -- could we see the dual spindles for the first time. This allowed us to provide an explanation for this 20-year-old mystery."

Mitosis is the process of cell division, when one cell splits into two daughter cells. It occurs throughout the lifespan of multi-cellular organisms but is particularly important when the organism grows and develops. The key step of mitosis is to pass an identical copy of the genome to the next cell generation. For this to happen, DNA is duplicated and organised into dense thread-like structures known as chromosomes. The chromosomes are then attached to long protein fibres -- organised into a spindle -- which pulls the chromosomes apart and triggers the formation of two new cells. {The following diagram is one which will likely be updated in future embryology textbooks.}

The spindle is made of thin, tube-like protein assemblies known as microtubules. During mitosis of animal cells, groups of such tubes grow dynamically and self-organize into a bi-polar spindle that surrounds the chromosomes. The microtubule fibres grow towards the chromosomes and connect with them, in preparation for chromosome separation to the daughter cells. Normally there is only one bi-polar spindle per cell, however, this research suggests that during the first cell division there are two: one each for the maternal and paternal chromosomes.

"The dual spindles provide a previously unknown mechanism -- and thus a possible explanation -- for the common mistakes we see in the first divisions of mammalian embryos," Dr. Ellenberg explains. Such mistakes can result in cells with multiple nuclei, terminating development. "Now, we have a new mechanism to go after and identify new molecular targets. It will be important to find out if it works the same in humans, because that could provide valuable information for research on how to improve human infertility treatment, for example."

In addition, the knowledge from this paper might impact legislation. In some countries, the law states that human life begins -- and is thus protected -- when the maternal and paternal nuclei fuse after fertilization. If it turns out that the dual spindle process works the same in humans, this definition is not fully accurate, as the union in one nucleus happens slightly later, after the first cell division.

This discovery would have been impossible without the light-sheet microscopy technology (as seen above) developed at EMBL, which is now available through the spin-off company Luxendo. This allows for real-time and 3D imaging of the early stages of development, when embryos are very sensitive to light and would be damaged by conventional light microscopy methods. The high speed and spatial precision of light-sheet microscopy drastically reduce the amount of light that the embryo is exposed to, making a detailed analysis of these formerly hidden processes possible.

This is one spin we can stay with for awhile.

Steph

Earthquake experiment with brownies representing the stable craton of Canada and jello representing the tectonic plate boundary in Haiti.

The kids made "earthquake-proof" structures and observed the differences of the structures on "Canada" and "Haiti."

funny.jpg)